"Discovering Sarah": An interview with Elizabeth Renker about her new podcast

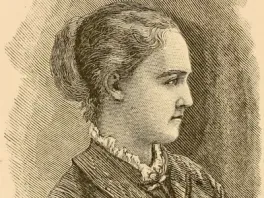

American poet Sarah Morgan Bryan Piatt (1836-1919) enjoyed a prolific career during her lifetime, widely acclaimed from the 1850s—when she was still a teenager—through the turn of the 20th century. She fell from view around the time of her death. In the 1990s, scholars rediscovered her work, quickly identifying her as a great woman poet akin to Emily Dickinson. Professor Elizabeth Renker has been focused on the Piatt recovery for 20 years and is now writing Piatt’s first biography. In summer 2022, she released season one of the podcast “Discovering Sarah: America’s Lost Great Writer.” We spoke with her about her Piatt projects.

Why did you choose the podcast format to share Sarah Morgan Bryan Piatt’s story?

The podcast medium is a great way to bring important stories about writers and literary history to a broad audience. As I’ve learned during more than 30 years of teaching and public speaking, many people are interested in stories about authors and literary history. This broad public audience doesn’t necessarily want to, or have the time to, wade through a lot of specialized scholarship. Of course, the ongoing quest to advance knowledge relies on scholarship written for a scholarly audience, but scholars like myself also design projects that speak to a public audience. Projects like my podcast are a vital way to share literature and literary history beyond the walls of universities. Related to the podcast, the Sarah Piatt Recovery Project that I created with the Ohio State Rare Books and Manuscripts Library is a fantastic resource as well, especially for those who want to go deeper into the research.

Normally, artists find even more success after their death than during their life. Why do you think the opposite was true for Piatt, at least for a while?

Sarah fell from public memory around the same time that women writers more generally were vanishing from the literary canon: roughly speaking, the 1920s. We use the term “canon” to refer to a culture’s understanding of which authors and books are most valuable—the ones that everyone “should” read, either in school or on their own. The canon changes at different points in history. There’s a lot of important scholarship on how the canon came into being and how it has evolved over time. The larger point is that, whatever the canon looks like at any particular moment, it arises from historical processes; it is not an eternal static list of timeless great works. Canons change over time as a result of cultural change. A great example that often surprises people is that Herman Melville was not classified as a “great author” until more than three decades after his death. Sarah also disappeared and is now being rediscovered. The neglect of women writers persisted across most of the 20th century. Efforts to recover women’s writing more generally gained significant traction in the 1980s. And Piatt’s rediscovery began in the 1990s.

Why do you feel passionate about Piatt and her work?

The most transformative and important thing that has happened in literature studies since the rise of the New Criticism in the 1930s is, in my view, the recovery of women writers and writers of color that began in the 1970s and finally gained significant traction in the 1980s. At one level, Piatt’s recovery is part of this larger history. But it’s important to stress that her recovery is also distinct in that she has emerged as a writer consistently described as “great,” a term used in this case to mean that she is a unique writer who stands out as a compelling voice and innovative artist in her time and our own. I agree with these assessments that Sarah Piatt is not only historically deserving of recovery (as are all these lost voices) but also that she is distinct, unique, unusual. She was and is an absolutely stunning literary artist, at the level of her poetic craft as well as in her shrewd commentary on the world she lived in. One thing that readers (including myself and my students) love about her is that her voice is often ironic. While her contemporaries often missed the irony, today’s readers “get” it more easily, especially once they have learned to read for it. I’ve been teaching her to undergrads for 20 years, and they adore her, especially her irony. She consistently tops the list on my end-of-term poll question “Who was your favorite writer this term?” We live in an age of irony. So our culture is primed to hear her voice now in a new and fresh way.

How did you find or connect with the other scholars who are featured in the episodes?

I found Sarah Piatt’s work because of the work done by prior scholars, especially Larry Michaels and Paula Bernat Bennett (first two episodes) and William Spengemann and Jessica Roberts (whom I hope to interview someday). I have been working on Piatt for 20 years, and for me it has been an essential part of the Piatt recovery to participate in a supportive community that works on shared interests as a team. Four of us recently published an essay called “Sarah Piatt and Community Scholarship” about how important it is for multiple people to pursue research about her, to support each other’s efforts, to talk about findings, and so on.

Community energy will help get out the word about Sarah Piatt. And there is simply too much to be done, too much to be discovered, to work on this important project without trying to draw in as many people as possible.

What do you hope listeners will take away from these podcasts?

That Sarah Piatt was a great writer in her own era and that her voice speaks directly to urgent issues today. She wrote about topics like oppression and resistance, about people on the margins, about women stuck in gender roles, about mothers and children, about Civil War and its aftermath, about colonial oppression, about radically different perspectives on the same event. And she had the keen eye of someone critical of social codes and structures of power even while aware that she lived inside them. My personal favorite poem, “Mock Diamonds,” is about the Old South, where she grew up. It was published during Reconstruction and reflects on the world of her youth that she left behind. In my view, it is the single best poem ever written depicting an emblematic Confederate soldier who won’t stay dead—even though the War is ostensibly over. Sarah Piatt called out then the problem that our nation is facing again right now.

Will there be more episodes in the future?

Oh, yes. I dropped the eight episodes of season one in July 2022, produced by English doctoral student Kayla Probeyahn. I hope to have season two ready for release in summer 2023.

If you had to recommend just one piece of Piatt’s work to listeners, what would it be?

I suggest her poem “The Palace-Burner,” which has been the gateway poem for many, including myself. This was the first poem of hers that I read—and after the first line, I think I said OMG aloud. I know others who had the same experience with this poem in particular. At the present time, “The Palace-Burner” is her signature poem, a term scholars use to mean the poem by which she is best known. “The Palace-Burner” is also a great example of her fierce examination of historical cataclysms, in this case, the Paris Commune of 1871, an uprising by working-class people who burned down the palace. Piatt’s poem meditates on a woman about to be executed for her revolutionary activities. The poem is about oppression, revolution, gender roles—and Piatt’s self-scrutiny for her own complicity in hegemony.